From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Benjamin Franklin FRS, FRSE (January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6, 1705] – April 17, 1790) was a renowned polymath and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, freemason, postmaster, scientist, inventor, humorist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat. As a scientist, he was a major figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics for his discoveries and theories regarding electricity. As an inventor, he is known for the lightning rod, bifocals, and the Franklin stove, among other inventions. He founded many civic organizations, including Philadelphia’s fire department and the University of Pennsylvania.

Franklin earned the title of “The First American” for his early and indefatigable campaigning for colonial unity, initially as an author and spokesman in London for several colonies. As the first United States Ambassador to France, he exemplified the emerging American nation. Franklin was foundational in defining the American ethos as a marriage of the practical values of thrift, hard work, education, community spirit, self-governing institutions, and opposition to authoritarianism both political and religious, with the scientific and tolerant values of the Enlightenment. In the words of historian Henry Steele Commager, “In a Franklin could be merged the virtues of Puritanism without its defects, the illumination of the Enlightenment without its heat.” To Walter Isaacson, this makes Franklin “the most accomplished American of his age and the most influential in inventing the type of society America would become.”

Franklin became a successful newspaper editor and printer in Philadelphia, the leading city in the colonies, publishing the Pennsylvania Gazette at the age of 23. He became wealthy publishing this and Poor Richard’s Almanack, which he authored under the pseudonym “Richard Saunders”. After 1767, he was associated with the Pennsylvania Chronicle, a newspaper that was known for its revolutionary sentiments and criticisms of the British policies.

He pioneered and was first president of Academy and College of Philadelphia which opened in 1751 and later became the University of Pennsylvania. He organized and was the first secretary of the American Philosophical Society and was elected president in 1769. Franklin became a national hero in America as an agent for several colonies when he spearheaded an effort in London to have the Parliament of Great Britain repeal the unpopular Stamp Act. An accomplished diplomat, he was widely admired among the French as American minister to Paris and was a major figure in the development of positive Franco-American relations. His efforts proved vital for the American Revolution in securing shipments of crucial munitions from France.

He was promoted to deputy postmaster-general for the British colonies in 1753, having been Philadelphia postmaster for many years, and this enabled him to set up the first national communications network. During the Revolution, he became the first United States Postmaster General. He was active in community affairs and colonial and state politics, as well as national and international affairs. From 1785 to 1788, he served as governor of Pennsylvania. He initially owned and dealt in slaves but, by the 1750s, he argued against slavery from an economic perspective and became one of the most prominent abolitionists.

His colorful life and legacy of scientific and political achievement, and his status as one of America’s most influential Founding Fathers, have seen Franklin honored more than two centuries after his death on coinage and the $100 bill, warships, and the names of many towns, counties, educational institutions, and corporations, as well as countless cultural references.

Ancestry

Benjamin Franklin’s father, Josiah Franklin, was a tallow chandler, a soap-maker and a candle-maker. Josiah was born at Ecton, Northamptonshire, England on December 23, 1657, the son of Thomas Franklin, a blacksmith-farmer, and Jane White. Benjamin’s mother, Abiah Folger, was born in Nantucket, Massachusetts, on August 15, 1667, to Peter Folger, a miller and schoolteacher, and his wife, Mary Morrell Folger, a former indentured servant.

Benjamin’s father and all four of his grandparents were born in England.

Josiah had seventeen children with his two wives. He married his first wife, Anne Child, in about 1677 in Ecton and immigrated with her to Boston in 1683; they had three children before immigrating, and four after. Following her death, Josiah was married to Abiah Folger on July 9, 1689 in the Old South Meeting House by Samuel Willard. Benjamin, their eighth child, was Josiah Franklin’s fifteenth child and tenth and last son.

Benjamin’s mother, Abiah, was born into a Puritan family that was among the first Pilgrims to flee to Massachusetts for religious freedom, when King Charles I of England began persecuting Puritans. They sailed for Boston in 1635. Her father was “the sort of rebel destined to transform colonial America.” As clerk of the court, he was jailed for disobeying the local magistrate in defense of middle-class shopkeepers and artisans in conflict with wealthy landowners. Ben Franklin followed in his grandfather’s footsteps in his battles against the wealthy Penn family that owned the Pennsylvania Colony.

Ancestors of Benjamin Franklin

Early life in Boston

Franklin’s birthplace on Milk Street, Boston, Massachusetts

Franklin’s birthplace site directly across from Old South Meeting House on Milk Street is commemorated by a bust above the second floor facade of this building.

Benjamin Franklin was born on Milk Street, in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 17, 1706, and baptized at Old South Meeting House. He was one of seventeen children born to Josiah Franklin, and one of ten born by Josiah’s second wife, Abiah Folger; the daughter of Peter Foulger and Mary Morrill. Among Benjamin’s siblings were his older brother James and his younger sister Jane.

Josiah wanted Ben to attend school with the clergy, but only had enough money to send him to school for two years. He attended Boston Latin School but did not graduate; he continued his education through voracious reading. Although “his parents talked of the church as a career” for Franklin, his schooling ended when he was ten. He worked for his father for a time, and at 12 he became an apprentice to his brother James, a printer, who taught Ben the printing trade. When Ben was 15, James founded The New-England Courant, which was the first truly independent newspaper in the colonies.

When denied the chance to write a letter to the paper for publication, Franklin adopted the pseudonym of “Silence Dogood”, a middle-aged widow. Mrs. Dogood’s letters were published, and became a subject of conversation around town. Neither James nor the Courant’s readers were aware of the ruse, and James was unhappy with Ben when he discovered the popular correspondent was his younger brother. Franklin was an advocate of free speech from an early age. When his brother was jailed for three weeks in 1722 for publishing material unflattering to the governor, young Franklin took over the newspaper and had Mrs. Dogood (quoting Cato’s Letters) proclaim: “Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom and no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech.” Franklin left his apprenticeship without his brother’s permission, and in so doing became a fugitive.

Franklin’s birthplace site directly across from Old South Meeting House on Milk Street is commemorated by a bust above the second floor facade of this building.

Philadelphia

La scuola della economia e della morale (1825)

At age 17, Franklin ran away to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, seeking a new start in a new city. When he first arrived, he worked in several printer shops around town, but he was not satisfied by the immediate prospects. After a few months, while working in a printing house, Franklin was convinced by Pennsylvania Governor Sir William Keith to go to London, ostensibly to acquire the equipment necessary for establishing another newspaper in Philadelphia. Finding Keith’s promises of backing a newspaper empty, Franklin worked as a typesetter in a printer’s shop in what is now the Church of St Bartholomew-the-Great in the Smithfield area of London. Following this, he returned to Philadelphia in 1726 with the help of Thomas Denham, a merchant who employed Franklin as clerk, shopkeeper, and bookkeeper in his business.

Junto and Library

In 1727, Benjamin Franklin, then 21, created the Junto, a group of “like minded aspiring artisans and tradesmen who hoped to improve themselves while they improved their community.” The Junto was a discussion group for issues of the day; it subsequently gave rise to many organizations in Philadelphia. The Junto was modeled after English coffeehouses that Franklin knew well, and which had become the center of the spread of Enlightenment ideas in Britain.

Reading was a great pastime of the Junto, but books were rare and expensive. The members created a library initially assembled from their own books after Franklin wrote:

A proposition was made by me that since our books were often referr’d to in our disquisitions upon the inquiries, it might be convenient for us to have them altogether where we met, that upon occasion they might be consulted; and by thus clubbing our books to a common library, we should, while we lik’d to keep them together, have each of us the advantage of using the books of all the other members, which would be nearly as beneficial as if each owned the whole.

This did not suffice, however. Franklin conceived the idea of a subscription library, which would pool the funds of the members to buy books for all to read. This was the birth of the Library Company of Philadelphia: its charter was composed by Franklin in 1731. In 1732, Franklin hired the first American librarian, Louis Timothee. The Library Company is now a great scholarly and research library.

Newspaperman

Benjamin Franklin (center) at work on a printing press. Reproduction of a Charles Mills painting by the Detroit Publishing Company.

Upon Denham’s death, Franklin returned to his former trade. In 1728, Franklin had set up a printing house in partnership with Hugh Meredith; the following year he became the publisher of a newspaper called The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Gazette gave Franklin a forum for agitation about a variety of local reforms and initiatives through printed essays and observations. Over time, his commentary, and his adroit cultivation of a positive image as an industrious and intellectual young man, earned him a great deal of social respect. But even after Franklin had achieved fame as a scientist and statesman, he habitually signed his letters with the unpretentious ‘B. Franklin, Printer.’

In 1732, Ben Franklin published the first German-language newspaper in America – Die Philadelphische Zeitung – although it failed after only one year, because four other newly founded German papers quickly dominated the newspaper market. Franklin printed Moravian religious books in German. Franklin often visited Bethlehem, Pennsylvania staying at the Moravian Sun Inn. In a 1751 pamphlet on demographic growth and its implications for the colonies, he called the Pennsylvania Germans “Palatine Boors” who could never acquire the “Complexion” of the English settlers and to “Blacks and Tawneys” as weakening the social structure of the colonies. Although Franklin apparently reconsidered shortly thereafter, and the phrases were omitted from all later printings of the pamphlet, his views may have played a role in his political defeat in 1764.

Franklin saw the printing press as a device to instruct colonial Americans in moral virtue. Frasca argues he saw this as a service to God, because he understood moral virtue in terms of actions, thus, doing good provides a service to God. Despite his own moral lapses, Franklin saw himself as uniquely qualified to instruct Americans in morality. He tried to influence American moral life through construction of a printing network based on a chain of partnerships from the Carolinas to New England. Franklin thereby invented the first newspaper chain. It was more than a business venture, for like many publishers since, he believed that the press had a public-service duty.

Coat of Arms of Benjamin Franklin

When Franklin established himself in Philadelphia, shortly before 1730, the town boasted two “wretched little” news sheets, Andrew Bradford’s The American Weekly Mercury, and Samuel Keimer’s Universal Instructor in all Arts and Sciences, and Pennsylvania Gazette. This instruction in all arts and sciences consisted of weekly extracts from Chambers’s Universal Dictionary. Franklin quickly did away with all this when he took over the Instructor and made it The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Gazette soon became Franklin’s characteristic organ, which he freely used for satire, for the play of his wit, even for sheer excess of mischief or of fun. From the first, he had a way of adapting his models to his own uses. The series of essays called “The Busy-Body”, which he wrote for Bradford’s American Mercury in 1729, followed the general Addisonian form, already modified to suit homelier conditions. The thrifty Patience, in her busy little shop, complaining of the useless visitors who waste her valuable time, is related to the ladies who address Mr. Spectator. The Busy-Body himself is a true Censor Morum, as Isaac Bickerstaff had been in the Tatler. And a number of the fictitious characters, Ridentius, Eugenius, Cato, and Cretico, represent traditional 18th-century classicism. Even this Franklin could use for contemporary satire, since Cretico, the “sowre Philosopher”, is evidently a portrait of Franklin’s rival, Samuel Keimer.

As time went on, Franklin depended less on his literary conventions, and more on his own native humor. In this there is a new spirit—not suggested to him by the fine breeding of Addison, or the bitter irony of Swift, or the stinging completeness of Pope. The brilliant little pieces Franklin wrote for his Pennsylvania Gazette have an imperishable place in American literature.

The Pennsylvania Gazette, like most other newspapers of the period, was often poorly printed. Franklin was busy with a hundred matters outside of his printing office, and never seriously attempted to raise the mechanical standards of his trade. Nor did he ever properly edit or collate the chance medley of stale items that passed for news in the Gazette. His influence on the practical side of journalism was minimal. On the other hand, his advertisements of books show his very great interest in popularizing secular literature. Undoubtedly his paper contributed to the broader culture that distinguished Pennsylvania from her neighbors before the Revolution. Like many publishers, Franklin built up a book shop in his printing office; he took the opportunity to read new books before selling them.

Franklin had mixed success in his plan to establish an inter-colonial network of newspapers that would produce a profit for him and disseminate virtue. He began in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1731. After the second editor died, his widow Elizabeth Timothy took over and made it a success, 1738–46. She was one of the colonial era’s first woman printers. For three decades Franklin maintained a close business relationship with her and her son Peter who took over in 1746. The Gazette had a policy of impartiality in political debates, while creating the opportunity for public debate, which encouraged others to challenge authority. Editor Peter Timothy avoided blandness and crude bias, and after 1765 increasingly took a patriotic stand in the growing crisis with Great Britain. However, Franklin’s Connecticut Gazette (1755–68) proved unsuccessful.

Freemason

In 1731, Franklin was initiated into the local Masonic lodge. He became Grand Master in 1734, indicating his rapid rise to prominence in Pennsylvania. That same year, he edited and published the first Masonic book in the Americas, a reprint of James Anderson’s Constitutions of the Free-Masons. Franklin remained a Freemason for the rest of his life.

Common-law marriage to Deborah Read

Deborah Read Franklin

(c. 1759). Common-law wife of Benjamin Franklin

Sarah Franklin Bache (1743–1808). Daughter of Benjamin Franklin and Deborah Read

At age 17 in 1723, Franklin proposed to 15-year-old Deborah Read while a boarder in the Read home. At that time, Read’s mother was wary of allowing her young daughter to marry Franklin, who was on his way to London at Governor Sir William Keith’s request, and also because of his financial instability. Her own husband had recently died, and she declined Franklin’s request to marry her daughter.

While Franklin was in London, his trip was extended, and there were problems with Sir William’s promises of support. Perhaps because of the circumstances of this delay, Deborah married a man named John Rodgers. This proved to be a regrettable decision. Rodgers shortly avoided his debts and prosecution by fleeing to Barbados with her dowry, leaving her behind. Rodgers’s fate was unknown, and because of bigamy laws, Deborah was not free to remarry.

Franklin established a common-law marriage with Deborah Read on September 1, 1730. They took in Franklin’s recently acknowledged young illegitimate son William and raised him in their household. They had two children together. Their son, Francis Folger Franklin, was born in October 1732 and died of smallpox in 1736. Their daughter, Sarah “Sally” Franklin, was born in 1743 and grew up to marry Richard Bache, have seven children, and look after her father in his old age.

Deborah’s fear of the sea meant that she never accompanied Franklin on any of his extended trips to Europe, and another possible reason why they spent so much time apart is that he may have blamed her for preventing their son Francis from being vaccinated against the disease that subsequently killed him. Deborah wrote to him in November 1769 saying she was ill due to “dissatisfied distress” from his prolonged absence, but he did not return until his business was done. Deborah Read Franklin died of a stroke in 1774, while Franklin was on an extended mission to England; he returned in 1775.

William Franklin

William Franklin

In 1730, 24-year-old Franklin publicly acknowledged the existence of his son William, who was deemed “illegitimate,” as he was born out of wedlock, and raised him in his household. His mother’s identity is unknown. He was educated in Philadelphia. Beginning at about age 30, William studied law in London in the early 1760s. He fathered an illegitimate son, William Temple Franklin, born February 22, 1762. The boy’s mother was never identified, and he was placed in foster care. Franklin later that year married Elizabeth Downes, daughter of a planter from Barbados. After William passed the bar, his father helped him gain an appointment in 1763 as the last Royal Governor of New Jersey.

A Loyalist, William and his father eventually broke relations over their differences about the American Revolutionary War. The elder Franklin could never accept William’s position. Deposed in 1776 by the revolutionary government of New Jersey, William was arrested at his home in Perth Amboy at the Proprietary House and imprisoned for a time. The younger Franklin went to New York in 1782, which was still occupied by British troops. He became leader of the Board of Associated Loyalists—a quasi-military organization, headquartered in New York City. They initiated guerrilla forays into New Jersey, southern Connecticut, and New York counties north of the city. When British troops evacuated from New York, William Franklin left with them and sailed to England. He settled in London, never to return to North America. In the preliminary peace talks in 1782 with Britain, “… Benjamin Franklin insisted that loyalists who had borne arms against the United States would be excluded from this plea (that they be given a general pardon). He was undoubtedly thinking of William Franklin.”

Success as an Author

Franklin’s The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle (Jan. 1741)

In 1733, Franklin began to publish the noted Poor Richard’s Almanack (with content both original and borrowed) under the pseudonym Richard Saunders, on which much of his popular reputation is based. Franklin frequently wrote under pseudonyms. Although it was no secret that Franklin was the author, his Richard Saunders character repeatedly denied it. “Poor Richard’s Proverbs”, adages from this almanac, such as “A penny saved is twopence dear” (often misquoted as “A penny saved is a penny earned”) and “Fish and visitors stink in three days”, remain common quotations in the modern world. Wisdom in folk society meant the ability to provide an apt adage for any occasion, and Franklin’s readers became well prepared. He sold about ten thousand copies per year—it became an institution. In 1741 Franklin began publishing The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle for all the British Plantations in America, the first such monthly magazine of this type published in America.

In 1758, the year he ceased writing for the Almanack, he printed Father Abraham’s Sermon, also known as The Way to Wealth. Franklin’s autobiography, begun in 1771 but published after his death, has become one of the classics of the genre.

Daylight saving time (DST) is often erroneously attributed to a 1784 satire that Franklin published anonymously. Modern DST was first proposed by George Vernon Hudson in 1895.

Inventions and scientific inquiries

Further information: Social contributions and studies by Benjamin Franklin

Franklin was a prodigious inventor. Among his many creations were the lightning rod, glass harmonica (a glass instrument, not to be confused with the metal harmonica), Franklin stove, bifocal glasses and the flexible urinary catheter. Franklin never patented his inventions; in his autobiography he wrote, “… as we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously.”

Electricity

Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky c. 1816 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, by Benjamin West

Franklin and Electricity vignette engraved by the BEP (c. 1860).

Franklin started exploring the phenomenon of electricity in 1746 when he saw some of Archibald Spencer’s lectures using static electricity for illustrations. Franklin proposed that “vitreous” and “resinous” electricity were not different types of “electrical fluid” (as electricity was called then), but the same “fluid” under different pressures. (The same proposal was made independently that same year by William Watson.) Franklin was the first to label them as positive and negative respectively, and he was the first to discover the principle of conservation of charge. In 1748 he constructed a multiple plate capacitor, that he called an “electrical battery” (not to be confused with Volta’s pile) by placing eleven panes of glass sandwiched between lead plates, suspended with silk cords and connected by wires.

In recognition of his work with electricity, Franklin received the Royal Society’s Copley Medal in 1753, and in 1756 he became one of the few 18th-century Americans elected as a Fellow of the Society. He received honorary degrees from Harvard and Yale universities (his first). The cgs unit of electric charge has been named after him: one franklin (Fr) is equal to one statcoulomb.

Franklin advised Harvard University in its acquisition of new electrical laboratory apparatus after the complete loss of its original collection, in a fire which destroyed the original Harvard Hall in 1764. The collection he assembled would later become part of the Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, now on public display in its Science Center.

Kite experiment and lightning rod

In 1750, he published a proposal for an experiment to prove that lightning is electricity by flying a kite in a storm that appeared capable of becoming a lightning storm. On May 10, 1752, Thomas-François Dalibard of France conducted Franklin’s experiment using a 40-foot-tall (12 m) iron rod instead of a kite, and he extracted electrical sparks from a cloud. On June 15 Franklin may possibly have conducted his well-known kite experiment in Philadelphia, successfully extracting sparks from a cloud. Franklin described the experiment in the Pennsylvania Gazette on October 19, 1752, without mentioning that he himself had performed it. This account was read to the Royal Society on December 21 and printed as such in the Philosophical Transactions. Joseph Priestley published details in his 1767 History and Present Status of Electricity. Franklin was careful to stand on an insulator, keeping dry under a roof to avoid the danger of electric shock. Others, such as Prof. Georg Wilhelm Richmann in Russia, were indeed electrocuted during the months following Franklin’s experiment.

In his writings, Franklin indicates that he was aware of the dangers and offered alternative ways to demonstrate that lightning was electrical, as shown by his use of the concept of electrical ground. Franklin did not perform this experiment in the way that is often pictured in popular literature, flying the kite and waiting to be struck by lightning, as it would have been dangerous. Instead he used the kite to collect some electric charge from a storm cloud, showing that lightning was electrical. On October 19 in a letter to England with directions for repeating the experiment, Franklin wrote:

When rain has wet the kite twine so that it can conduct the electric fire freely, you will find it streams out plentifully from the key at the approach of your knuckle, and with this key a phial, or Leyden jar, may be charged: and from electric fire thus obtained spirits may be kindled, and all other electric experiments [may be] performed which are usually done by the help of a rubber glass globe or tube; and therefore the sameness of the electrical matter with that of lightening completely demonstrated.

Franklin’s electrical experiments led to his invention of the lightning rod. He noted that conductors with a sharp rather than a smooth point could discharge silently, and at a far greater distance. He surmised that this could help protect buildings from lightning by attaching “upright Rods of Iron, made sharp as a Needle and gilt to prevent Rusting, and from the Foot of those Rods a Wire down the outside of the Building into the Ground; … Would not these pointed Rods probably draw the Electrical Fire silently out of a Cloud before it came nigh enough to strike, and thereby secure us from that most sudden and terrible Mischief!” Following a series of experiments on Franklin’s own house, lightning rods were installed on the Academy of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania) and the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) in 1752.

Population Studies

Franklin had a major influence on the emerging science of demography, or population studies. Thomas Malthus is noted for his rule of population growth and credited Franklin for discovering it. Kammen (1990) and Drake (2011) say Franklin’s “Observations on the Increase of Mankind” (1755) stands alongside Ezra Stiles’ “Discourse on Christian Union” (1760) as the leading works of eighteenth-century Anglo-American demography; Drake credits Franklin’s “wide readership and prophetic insight.”

In the 1730s and 1740s, Franklin began taking notes on population growth, finding that the American population had the fastest growth rates on earth. Emphasizing that population growth depended on food supplies—a line of thought later developed by Thomas Malthus—Franklin emphasized the abundance of food and available farmland in America. He calculated that America’s population was doubling every twenty years and would surpass that of England in a century. In 1751, he drafted “Observations concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, &c.” Four years later, it was anonymously printed in Boston, and it was quickly reproduced in Britain, where it influenced the economists Adam Smith and later Thomas Malthus. Franklin’s predictions alarmed British leaders who did not want to be surpassed by the colonies, so they became more willing to impose restrictions on the colonial economy.

Franklin was also a pioneer in the study of slave demography, as shown in his 1755 essay.

Atlantic Ocean Currents

As deputy postmaster, Franklin became interested in the North Atlantic Ocean circulation patterns. While in England in 1768, he heard a complaint from the Colonial Board of Customs: Why did it take British packet ships carrying mail several weeks longer to reach New York than it took an average merchant ship to reach Newport, Rhode Island? The merchantmen had a longer and more complex voyage because they left from London, while the packets left from Falmouth in Cornwall.

Franklin put the question to his cousin Timothy Folger, a Nantucket whaler captain, who told him that merchant ships routinely avoided a strong eastbound mid-ocean current. The mail packet captains sailed dead into it, thus fighting an adverse current of 3 miles per hour (5 km/h). Franklin worked with Folger and other experienced ship captains, learning enough to chart the current and name it the Gulf Stream, by which it is still known today.

Franklin published his Gulf Stream chart in 1770 in England, where it was completely ignored. Subsequent versions were printed in France in 1778 and the U.S. in 1786. The British edition of the chart, which was the original, was so thoroughly ignored that everyone assumed it was lost forever until Phil Richardson, a Woods Hole oceanographer and Gulf Stream expert, discovered it in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris in 1980. This find received front-page coverage in the New York Times.

It took many years for British sea captains to adopt Franklin’s advice on navigating the current; once they did, they were able to trim two weeks from their sailing time. In 1853, the oceanographer and cartographer Matthew Fontaine Maury noted that while Franklin charted and codified the Gulf Stream, he did not discover it:

Though it was Dr. Franklin and Captain Tim Folger, who first turned the Gulf Stream to nautical account, the discovery that there was a Gulf Stream cannot be said to belong to either of them, for its existence was known to Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, and to Sir Humphrey Gilbert, in the 16th century.

Wave theory of light

Franklin was, along with his contemporary Leonhard Euler, the only major scientist who supported Christiaan Huygens’s wave theory of light, which was basically ignored by the rest of the scientific community. In the 18th century Newton’s corpuscular theory was held to be true; only after Young’s well-known slit experiment in 1803 were most scientists persuaded to believe Huygens’s theory.

Meteorology

On October 21, 1743, according to popular myth, a storm moving from the southwest denied Franklin the opportunity of witnessing a lunar eclipse. Franklin was said to have noted that the prevailing winds were actually from the northeast, contrary to what he had expected. In correspondence with his brother, Franklin learned that the same storm had not reached Boston until after the eclipse, despite the fact that Boston is to the northeast of Philadelphia. He deduced that storms do not always travel in the direction of the prevailing wind, a concept that greatly influenced meteorology.

After the Icelandic volcanic eruption of Laki in 1783, and the subsequent harsh European winter of 1784, Franklin made observations connecting the causal nature of these two separate events. He wrote about them in a lecture series.

Traction kiting

Though Benjamin Franklin has been most noted kite-wise with his lightning experiments, he has also been noted by many for his using kites to pull humans and ships across waterways. The George Pocock in the book A TREATISE on The Aeropleustic Art, or Navigation in the Air, by means of Kites, or Buoyant Sails noted being inspired by Benjamin Franklin’s traction of his body by kite power across a waterway. In his later years he suggested using the technique for pulling ships.

Concept of cooling

Franklin noted a principle of refrigeration by observing that on a very hot day, he stayed cooler in a wet shirt in a breeze than he did in a dry one. To understand this phenomenon more clearly Franklin conducted experiments. In 1758 on a warm day in Cambridge, England, Franklin and fellow scientist John Hadley experimented by continually wetting the ball of a mercury thermometer with ether and using bellows to evaporate the ether. With each subsequent evaporation, the thermometer read a lower temperature, eventually reaching 7 °F (−14 °C). Another thermometer showed that the room temperature was constant at 65 °F (18 °C). In his letter Cooling by Evaporation, Franklin noted that, “One may see the possibility of freezing a man to death on a warm summer’s day.”

Temperature’s effect on electrical conductivity

According to Michael Faraday, Franklin’s experiments on the non-conduction of ice are worth mentioning, although the law of the general effect of liquefaction on electrolytes is not attributed to Franklin. However, as reported in 1836 by Prof. A. D. Bache of the University of Pennsylvania, the law of the effect of heat on the conduction of bodies otherwise non-conductors, for example, glass, could be attributed to Franklin. Franklin writes, “… A certain quantity of heat will make some bodies good conductors, that will not otherwise conduct …” and again, “… And water, though naturally a good conductor, will not conduct well when frozen into ice.”

Oceanography findings

An illustration from Franklin’s paper on “Water-spouts and Whirlwinds”

An aging Franklin accumulated all his oceanographic findings in Maritime Observations, published by the Philosophical Society’s transactions in 1786. It contained ideas for sea anchors, catamaran hulls, watertight compartments, shipboard lightning rods and a soup bowl designed to stay stable in stormy weather.

Decision-making

In a 1772 letter to Joseph Priestley, Franklin lays out the earliest known description of the Pro & Con list, a common decision-making technique, now sometimes called a decisional balance sheet:

… my Way is, to divide half a Sheet of Paper by a Line into two Columns, writing over the one Pro, and over the other Con. Then during three or four Days Consideration I put down under the different Heads short Hints of the different Motives that at different Times occur to me for or against the Measure. When I have thus got them all together in one View, I endeavour to estimate their respective Weights; and where I find two, one on each side, that seem equal, I strike them both out: If I find a Reason pro equal to some two Reasons con, I strike out the three. If I judge some two Reasons con equal to some three Reasons pro, I strike out the five; and thus proceeding I find at length where the Ballance lies; and if after a Day or two of farther Consideration nothing new that is of Importance occurs on either side, I come to a Determination accordingly.

Oil on water

While traveling on a ship, Franklin had observed that the wake of a ship was diminished when the cooks scuttled their greasy water. He studied the effects on a large pond in Clapham Common, London. “I fetched out a cruet of oil and dropt a little of it on the water … though not more than a teaspoon full, produced an instant calm over a space of several yards square.” He later used the trick to “calm the waters” by carrying “a little oil in the hollow joint of my cane”.

Musical endeavors

Glass harmonica

Franklin is known to have played the violin, the harp, and the guitar. He also composed music, notably a string quartet in early classical style. He developed a much-improved version of the glass harmonica, in which the glasses rotate on a shaft, with the player’s fingers held steady, instead of the other way around; this version soon found its way to Europe.

Chess

Franklin was an avid chess player. He was playing chess by around 1733, making him the first chess player known by name in the American colonies. His essay on “The Morals of Chess” in Columbian magazine in December 1786 is the second known writing on chess in America. This essay in praise of chess and prescribing a code of behavior for the game has been widely reprinted and translated. He and a friend also used chess as a means of learning the Italian language, which both were studying; the winner of each game between them had the right to assign a task, such as parts of the Italian grammar to be learned by heart, to be performed by the loser before their next meeting.

Franklin was able to play chess more frequently against stronger opposition during his many years as a civil servant and diplomat in England, where the game was far better established than in America. He was able to improve his playing standard by facing more experienced players during this period. He regularly attended Old Slaughter’s Coffee House in London for chess and socializing, making many important personal contacts. While in Paris, both as a visitor and later as ambassador, he visited the famous Café de la Régence, which France’s strongest players made their regular meeting place. No records of his games have survived, so it is not possible to ascertain his playing strength in modern terms.

Franklin was inducted into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame in 1999. The Franklin Mercantile Chess Club in Philadelphia, the second oldest chess club in the U.S., is named in his honor.

Public Life

Early steps in Pennsylvania

Join, or Die: This political cartoon by Franklin urged the colonies to join together during the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War).

In 1736, Franklin created the Union Fire Company, one of the first volunteer firefighting companies in America. In the same year, he printed a new currency for New Jersey based on innovative anti-counterfeiting techniques he had devised. Throughout his career, Franklin was an advocate for paper money, publishing A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency in 1729, and his printer printed money. He was influential in the more restrained and thus successful monetary experiments in the Middle Colonies, which stopped deflation without causing excessive inflation. In 1766 he made a case for paper money to the British House of Commons.

As he matured, Franklin began to concern himself more with public affairs. In 1743, he first devised a scheme for The Academy, Charity School, and College of Philadelphia. However, the person he had in mind to run the academy, Rev. Richard Peters, refused and Franklin put his ideas away until 1749, when he printed his own pamphlet, Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania. He was appointed president of the Academy on November 13, 1749; the Academy and the Charity School opened on August 13, 1751.

In 1743, Franklin founded the American Philosophical Society to help scientific men discuss their discoveries and theories. He began the electrical research that, along with other scientific inquiries, would occupy him for the rest of his life, in between bouts of politics and moneymaking.

In 1747, Franklin (already a very wealthy man) retired from printing and went into other businesses. He created a partnership with his foreman, David Hall, which provided Franklin with half of the shop’s profits for 18 years. This lucrative business arrangement provided leisure time for study, and in a few years he had made discoveries that gave him a reputation with educated persons throughout Europe and especially in France.

Franklin became involved in Philadelphia politics and rapidly progressed. In October 1748, he was selected as a councilman, in June 1749 he became a Justice of the Peace for Philadelphia, and in 1751 he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly. On August 10, 1753, Franklin was appointed deputy postmaster-general of British North America, (see below). His most notable service in domestic politics was his reform of the postal system, with mail sent out every week.

Pennsylvania Hospital by William Strickland, 1755

In 1751, Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond obtained a charter from the Pennsylvania legislature to establish a hospital. Pennsylvania Hospital was the first hospital in what was to become the United States of America.

In 1752, Franklin organized the Philadelphia Contributionship, the first homeowner’s insurance company in what would become the United States.

Between 1750 and 1753, the “educational triumvirate” of Dr. Benjamin Franklin, the American Dr. Samuel Johnson of Stratford, Connecticut, and the immigrant Scottish schoolteacher Dr. William Smith built on Franklin’s initial scheme and created what Bishop James Madison, president of the College of William & Mary, called a “new-model” plan or style of American college. Franklin solicited, printed in 1752, and promoted an American textbook of moral philosophy from the American Dr. Samuel Johnson titled Elementa Philosophica to be taught in the new colleges to replace courses in denominational divinity.

Seal of the College of Philadelphia

In June 1753, Johnson, Franklin, and Smith met in Stratford. They decided the new-model college would focus on the professions, with classes taught in English instead of Latin, have subject matter experts as professors instead of one tutor leading a class for four years, and there would be no religious test for admission. Johnson went on to found King’s College (now Columbia University) in New York City in 1754, while Franklin hired Smith as Provost of the College of Philadelphia, which opened in 1755. At its first commencement, on May 17, 1757, seven men graduated; six with a Bachelor of Arts and one as Master of Arts. It was later merged with the University of the State of Pennsylvania to become the University of Pennsylvania. The College was to become influential in guiding the founding documents of the United States: in the Continental Congress, for example, over one third of the college-affiliated men who contributed the Declaration of Independence between September 4, 1774, and July 4, 1776, were affiliated with the College.

In 1753, both Harvard and Yale awarded him honorary degrees.

In 1754, he headed the Pennsylvania delegation to the Albany Congress. This meeting of several colonies had been requested by the Board of Trade in England to improve relations with the Indians and defense against the French. Franklin proposed a broad Plan of Union for the colonies. While the plan was not adopted, elements of it found their way into the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution.

Sketch of the original Tun Tavern

In 1756, Franklin organized the Pennsylvania Militia (see “Associated Regiment of Philadelphia” under heading of Pennsylvania’s 103rd Artillery and 111th Infantry Regiment at Continental Army). He used Tun Tavern as a gathering place to recruit a regiment of soldiers to go into battle against the Native American uprisings that beset the American colonies. Reportedly Franklin was elected “Colonel” of the Associated Regiment but declined the honor.

Decades in London

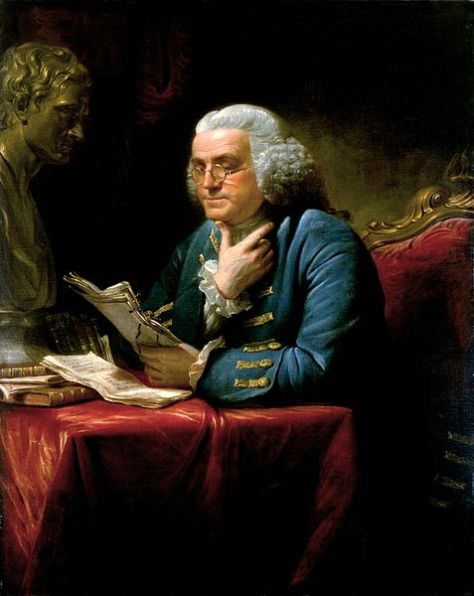

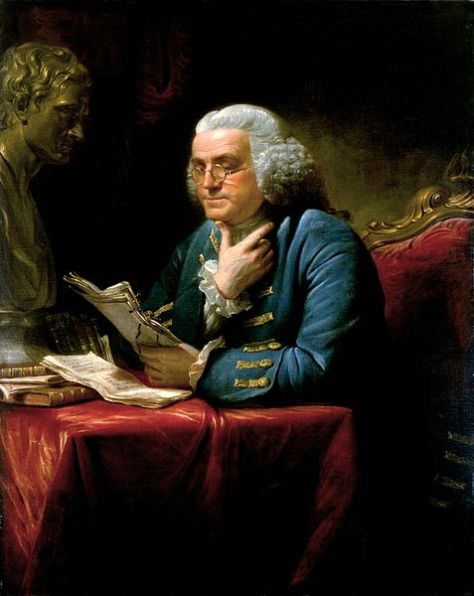

Franklin in London, 1767, wearing a blue suit with elaborate gold braid and buttons, a far cry from the simple dress he affected at the French court in later years. Painting by David Martin, displayed in the White House.

From the mid 1750s to the mid 1770s, Franklin spent much of his time in London. Officially he was there on a political mission, but he used his time to further his scientific explorations as well, meeting many notable people.

In 1757, he was sent to England by the Pennsylvania Assembly as a colonial agent to protest against the political influence of the Penn family, the proprietors of the colony. He remained there for five years, striving to end the proprietors’ prerogative to overturn legislation from the elected Assembly, and their exemption from paying taxes on their land. His lack of influential allies in Whitehall led to the failure of this mission.

At this time, many members of the Pennsylvania Assembly were feuding with William Penn’s heirs, who controlled the colony as proprietors. After his return to the colony, Franklin led the “anti-proprietary party” in the struggle against the Penn family, and was elected Speaker of the Pennsylvania House in May 1764. His call for a change from proprietary to royal government was a rare political miscalculation, however: Pennsylvanians worried that such a move would endanger their political and religious freedoms. Because of these fears, and because of political attacks on his character, Franklin lost his seat in the October 1764 Assembly elections. The anti-proprietary party dispatched Franklin to England again to continue the struggle against the Penn family proprietorship. During this trip, events drastically changed the nature of his mission.

Pennsylvania colonial currency printed by Franklin in 1764

In London, Franklin opposed the 1765 Stamp Act. Unable to prevent its passage, he made another political miscalculation and recommended a friend to the post of stamp distributor for Pennsylvania. Pennsylvanians were outraged, believing that he had supported the measure all along, and threatened to destroy his home in Philadelphia. Franklin soon learned of the extent of colonial resistance to the Stamp Act, and he testified during the House of Commons proceedings that led to its repeal.

With this, Franklin suddenly emerged as the leading spokesman for American interests in England. He wrote popular essays on behalf of the colonies. Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts also appointed him as their agent to the Crown.

Franklin lodged in a house in Craven Street, just off The Strand in central London. During his stays there, he developed a close friendship with his landlady, Margaret Stevenson, and her circle of friends and relations, in particular her daughter Mary, who was more often known as Polly. Their house, which he used on various lengthy missions from 1757 to 1775, is the only one of his residences to survive. It opened to the public as the Benjamin Franklin House museum in 2006.

Whilst in London, Franklin became involved in radical politics. He belonged to a gentleman’s club (which he called “the honest Whigs”), which held stated meetings, and included members such as Richard Price, the minister of Newington Green Unitarian Church who ignited the Revolution Controversy, and Andrew Kippis.

In 1756, Franklin had become a member of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (now the Royal Society of Arts or RSA), which had been founded in 1754 and whose early meetings took place in Covent Garden coffee shops. After his return to the United States in 1775, Franklin became the Society’s Corresponding Member, continuing a close connection. The RSA instituted a Benjamin Franklin Medal in 1956 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of his birth and the 200th anniversary of his membership of the RSA.

The study of natural philosophy (what we would call science) drew him into overlapping circles of acquaintance. Franklin was, for example, a corresponding member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, which included such other scientific and industrial luminaries as Matthew Boulton, James Watt, Josiah Wedgwood and Erasmus Darwin; on occasion he visited them.

In 1759, the University of St Andrews awarded Franklin an honorary doctorate in recognition of his accomplishments. He was also awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University in 1762. Because of these honors, Franklin was often addressed as “Dr. Franklin.”

Franklin also managed to secure an appointed post for his illegitimate son, William Franklin, by then an attorney, as Colonial Governor of New Jersey.

While living in London in 1768, he developed a phonetic alphabet in A Scheme for a new Alphabet and a Reformed Mode of Spelling. This reformed alphabet discarded six letters Franklin regarded as redundant (c, j, q, w, x, and y), and substituted six new letters for sounds he felt lacked letters of their own. His new alphabet, however, never caught on, and he eventually lost interest.

Travels around Britain and Ireland

Franklin used London as a base to travel. In 1771, he made short journeys through different parts of England, staying with Joseph Priestley at Leeds, Thomas Percival at Manchester and Erasmus Darwin at Lichfield.

In Scotland, he spent five days with Lord Kames near Stirling and stayed for three weeks with David Hume in Edinburgh. In 1759, he visited Edinburgh with his son, and recalled his conversations there as “the densest happiness of my life”. In February 1759, the University of St Andrews awarded him an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree. From then he was known as “Doctor Franklin”. In October of the same year he was granted Freedom of the Borough of St Andrews.

He had never been to Ireland before, and met and stayed with Lord Hillsborough, who he believed was especially attentive. Franklin noted of him that “all the plausible behaviour I have described is meant only, by patting and stroking the horse, to make him more patient, while the reins are drawn tighter, and the spurs set deeper into his sides.” In Dublin, Franklin was invited to sit with the members of the Irish Parliament rather than in the gallery. He was the first American to receive this honor. While touring Ireland, he was moved by the level of poverty he saw. Ireland’s economy was affected by the same trade regulations and laws of Britain that governed America. Franklin feared that America could suffer the same effects should Britain’s “colonial exploitation” continue.

Visits to Europe

Franklin spent two months in German lands in 1766, but his connections to the country stretched across a lifetime. He declared a debt of gratitude to German scientist Otto von Guericke for his early studies of electricity. Franklin also co-authored the first treaty of friendship between Prussia and America in 1785.

In September 1767, Franklin visited Paris with his usual traveling partner, Sir John Pringle. News of his electrical discoveries was widespread in France. His reputation meant that he was introduced to many influential scientists and politicians, and also to King Louis XV.

Defending the American cause

One line of argument in Parliament was that Americans should pay a share of the costs of the French and Indian War, and that therefore taxes should be levied on them. Franklin became the American spokesman in highly publicized testimony in Parliament in 1766. He stated that Americans already contributed heavily to the defense of the Empire. He said local governments had raised, outfitted and paid 25,000 soldiers to fight France—as many as Britain itself sent—and spent many millions from American treasuries doing so in the French and Indian War alone.

In 1773, Franklin published two of his most celebrated pro-American satirical essays: “Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One”, and “An Edict by the King of Prussia”.

Hutchinson letters leak

In June 1773 Franklin obtained private letters of Thomas Hutchinson and Andrew Oliver, governor and lieutenant governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, that proved they were encouraging the Crown to crack down on Bostonians. Franklin sent them to America, where they escalated the tensions. The letters were finally leaked to the public in the Boston Gazette in mid-June 1773, causing a political firestorm in Massachusetts and raising significant questions in England. The British began to regard him as the fomenter of serious trouble. Hopes for a peaceful solution ended as he was systematically ridiculed and humiliated by Solicitor-General Alexander Wedderburn, before the Privy Council on January 29, 1774. He returned to Philadelphia in March 1775, and abandoned his accommodationist stance.

Coming of revolution

In 1763, soon after Franklin returned to Pennsylvania from England for the first time, the western frontier was engulfed in a bitter war known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. The Paxton Boys, a group of settlers convinced that the Pennsylvania government was not doing enough to protect them from American Indian raids, murdered a group of peaceful Susquehannock Indians and marched on Philadelphia. Franklin helped to organize a local militia to defend the capital against the mob. He met with the Paxton leaders and persuaded them to disperse. Franklin wrote a scathing attack against the racial prejudice of the Paxton Boys. “If an Indian injures me”, he asked, “does it follow that I may revenge that Injury on all Indians?”

He provided an early response to British surveillance through his own network of counter-surveillance and manipulation. “He waged a public relations campaign, secured secret aid, played a role in privateering expeditions, and churned out effective and inflammatory propaganda.”

Declaration of Independence

About 50 men, most of them seated, are in a large meeting room. Most are focused on the five men standing in the center of the room. The tallest of the five is laying a document on a table.

John Trumbull depicts the Committee of Five presenting their work to the Congress.

By the time Franklin arrived in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, after his second mission to Great Britain, the American Revolution had begun—with fighting between colonials and British at Lexington and Concord. The New England militia had trapped the main British army in Boston. The Pennsylvania Assembly unanimously chose Franklin as their delegate to the Second Continental Congress. In June 1776, he was appointed a member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence. Although he was temporarily disabled by gout and unable to attend most meetings of the Committee, Franklin made several “small but important” changes to the draft sent to him by Thomas Jefferson.

At the signing, he is quoted as having replied to a comment by Hancock that they must all hang together: “Yes, we must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

Postmaster

Benjamin Franklin First US postage stamp Issue of 1847

Well known as a printer and publisher, Franklin was appointed postmaster of Philadelphia in 1737, holding the office until 1753, when he and publisher William Hunter were named deputy postmasters–general of British North America, the first to hold the office. (Joint appointments were standard at the time, for political reasons.) Franklin was responsible for the British colonies from Pennsylvania north and east, as far as the island of Newfoundland. A post office for local and outgoing mail had been established in Halifax, Nova Scotia, by local stationer Benjamin Leigh, on April 23, 1754, but service was irregular. Franklin opened the first post office to offer regular, monthly mail in what would later become Canada, at Halifax, on December 9, 1755. Meantime, Hunter became postal administrator in Williamsburg, Virginia and oversaw areas south of Annapolis, Maryland. Franklin reorganized the service’s accounting system, then improved speed of delivery between Philadelphia, New York and Boston. By 1761, efficiencies led to the first profits for the colonial post office.

Benjamin Franklin on a Canada Post stamp of 2013, with colonial Quebec City in background

When the lands of New France were ceded to the British under the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the new British province of Quebec was created among them, and Franklin saw mail service expanded between Montreal, Trois-Rivières, Quebec City, and New York. For the greater part of his appointment, Franklin lived in England (from 1757 to 1762, and again from 1764 to 1774)—about three-quarters of his term. Eventually, his sympathies for the rebel cause in the American Revolution led to his dismissal on January 31, 1774.

On July 26, 1775, the Second Continental Congress established the United States Post Office and named Benjamin Franklin as the first United States Postmaster General. Franklin had been a postmaster for decades and was a natural choice for the position. He had just returned from England and was appointed chairman of a Committee of Investigation to establish a postal system. The report of the Committee, providing for the appointment of a postmaster general for the 13 American colonies, was considered by the Continental Congress on July 25 and 26. On July 26, 1775, Franklin was appointed Postmaster General, the first appointed under the Continental Congress. It established a postal system that became the United States Post Office, a system that continues to operate today.

Ambassador to France: 1776–1785

Franklin, in his fur hat, charmed the French with what they perceived as rustic New World genius.

In December 1776, Franklin was dispatched to France as commissioner for the United States. He took with him as secretary his 16-year-old grandson, William Temple Franklin. They lived in a home in the Parisian suburb of Passy, donated by Jacques-Donatien Le Ray de Chaumont, who supported the United States. Franklin remained in France until 1785. He conducted the affairs of his country toward the French nation with great success, which included securing a critical military alliance in 1778 and negotiating the Treaty of Paris (1783).

Among his associates in France was Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau—a French Revolutionary writer, orator and statesman who in early 1791 would be elected president of the National Assembly. In July 1784, Franklin met with Mirabeau and contributed anonymous materials that the Frenchman used in his first signed work: Considerations sur l’ordre de Cincinnatus. The publication was critical of the Society of the Cincinnati, established in the United States. Franklin and Mirabeau thought of it as a “noble order”, inconsistent with the egalitarian ideals of the new republic.

During his stay in France, Benjamin Franklin was active as a Freemason, serving as Venerable Master of the Lodge Les Neuf Sœurs from 1779 until 1781. He was the 106th member of the Lodge. In 1784, when Franz Mesmer began to publicize his theory of “animal magnetism” which was considered offensive by many, Louis XVI appointed a commission to investigate it. These included the chemist Antoine Lavoisier, the physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, the astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly, and Benjamin Franklin. In 1781, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

While in France Franklin designed and commissioned Augustin Dupré to engrave the medallion “Libertas Americana” minted in Paris in 1783.

Franklin’s advocacy for religious tolerance in France contributed to arguments made by French philosophers and politicians that resulted in Louis XVI’s signing of the Edict of Versailles in November 1787. This edict effectively nullified the Edict of Fontainebleau, which had denied non-Catholics civil status and the right to openly practice their faith.

Franklin also served as American minister to Sweden, although he never visited that country. He negotiated a treaty that was signed in April 1783. On August 27, 1783, in Paris, Franklin witnessed the world’s first hydrogen balloon flight. Le Globe, created by professor Jacques Charles and Les Frères Robert, was watched by a vast crowd as it rose from the Champ de Mars (now the site of the Eiffel Tower). Franklin became so enthusiastic that he subscribed financially to the next project to build a manned hydrogen balloon. On December 1, 1783, Franklin was seated in the special enclosure for honoured guests when La Charlière took off from the Jardin des Tuileries, piloted by Jacques Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert.

Constitutional Convention

Franklin’s return to Philadelphia, 1785, by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

When he returned home in 1785, Franklin occupied a position only second to that of George Washington as the champion of American independence. Le Ray honored him with a commissioned portrait painted by Joseph Duplessis, which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. After his return, Franklin became an abolitionist and freed his two slaves. He eventually became president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society.

In 1787, Franklin served as a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention. He held an honorary position and seldom engaged in debate. He is the only Founding Father who is a signatory of all four of the major documents of the founding of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Alliance with France, the Treaty of Paris and the United States Constitution.

In 1787, a group of prominent ministers in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, proposed the foundation of a new college named in Franklin’s honor. Franklin donated £200 towards the development of Franklin College (now called Franklin & Marshall College).

Between 1771 and 1788, he finished his autobiography. While it was at first addressed to his son, it was later completed for the benefit of mankind at the request of a friend.

Franklin strongly supported the right to freedom of speech:

In those wretched countries where a man cannot call his tongue his own, he can scarce call anything his own. Whoever would overthrow the liberty of a nation must begin by subduing the freeness of speech … Without freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom, and no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech, which is the right of every man …

— Silence Dogood no. 8, 1722

President of Pennsylvania

Franklin autograph check signed during his Presidency of Pennsylvania

Special balloting conducted October 18, 1785, unanimously elected Franklin the sixth president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, replacing John Dickinson. The office was practically that of governor. Franklin held that office for slightly over three years, longer than any other, and served the constitutional limit of three full terms. Shortly after his initial election he was reelected to a full term on October 29, 1785, and again in the fall of 1786 and on October 31, 1787. In that capacity he served as host to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia.

Virtue, religion, and personal beliefs

A bust of Franklin by Jean-Antoine Houdon

Voltaire blessing Franklin’s grandson, in the name of God and Liberty, by Pedro Américo

Benjamin Franklin by Hiram Powers

Like the other advocates of republicanism, Franklin emphasized that the new republic could survive only if the people were virtuous. All his life he explored the role of civic and personal virtue, as expressed in Poor Richard’s aphorisms. Franklin felt that organized religion was necessary to keep men good to their fellow men, but rarely attended religious services himself. When Franklin met Voltaire in Paris and asked his fellow member of the Enlightenment vanguard to bless his grandson, Voltaire said in English, “God and Liberty”, and added, “this is the only appropriate benediction for the grandson of Monsieur Franklin.”

Franklin’s parents were both pious Puritans. The family attended the Old South Church, the most liberal Puritan congregation in Boston, where Benjamin Franklin was baptized in 1706. Franklin’s father, a poor chandler, owned a copy of a book, Bonifacius: Essays to Do Good, by the Puritan preacher and family friend Cotton Mather, which Franklin often cited as a key influence on his life. Franklin’s first pen name, Silence Dogood, paid homage both to the book and to a widely known sermon by Mather. The book preached the importance of forming voluntary associations to benefit society. Franklin learned about forming do-good associations from Cotton Mather, but his organizational skills made him the most influential force in making voluntarism an enduring part of the American ethos.

Franklin formulated a presentation of his beliefs and published it in 1728. It did not mention many of the Puritan ideas as regards belief in salvation, the divinity of Jesus, and indeed most religious dogma. He clarified himself as a deist in his 1771 autobiography, although he still considered himself a Christian. He retained a strong faith in a God as the wellspring of morality and goodness in man, and as a Providential actor in history responsible for American independence.

It was Ben Franklin who, at a critical impasse during the Constitutional Convention in June 1787, attempted to introduce the practice of daily common prayer with these words:

… In the beginning of the contest with G. Britain, when we were sensible of danger we had daily prayer in this room for the Divine Protection. Our prayers, Sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered. All of us who were engaged in the struggle must have observed frequent instances of a Superintending providence in our favor. … And have we now forgotten that powerful friend? or do we imagine that we no longer need His assistance. I have lived, Sir, a long time and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth—that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings that “except the Lord build they labor in vain that build it.” I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without his concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel: … I therefore beg leave to move—that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business, and that one or more of the Clergy of this City be requested to officiate in that service.

However, the motion met with resistance and was never brought to a vote.

Franklin was an enthusiastic supporter of the evangelical minister George Whitefield during the First Great Awakening. Franklin did not subscribe to Whitefield’s theology, but he admired Whitefield for exhorting people to worship God through good works. Franklin published all of Whitefield’s sermons and journals, thereby earning a lot of money and boosting the Great Awakening.

When he stopped attending church, Franklin wrote in his autobiography:

… Sunday being my studying day, I never was without some religious principles. I never doubted, for instance, the existence of the Deity; that He made the world, and governed it by His providence; that the most acceptable service of God was the doing good to man; that our souls are immortal; and that all crime will be punished, and virtue rewarded, either here or hereafter.

Franklin retained a lifelong commitment to the Puritan virtues and political values he had grown up with, and through his civic work and publishing, he succeeded in passing these values into the American culture permanently. He had a “passion for virtue”. These Puritan values included his devotion to egalitarianism, education, industry, thrift, honesty, temperance, charity and community spirit.

The classical authors read in the Enlightenment period taught an abstract ideal of republican government based on hierarchical social orders of king, aristocracy and commoners. It was widely believed that English liberties relied on their balance of power, but also hierarchal deference to the privileged class. “Puritanism … and the epidemic evangelism of the mid-eighteenth century, had created challenges to the traditional notions of social stratification” by preaching that the Bible taught all men are equal, that the true value of a man lies in his moral behavior, not his class, and that all men can be saved. Franklin, steeped in Puritanism and an enthusiastic supporter of the evangelical movement, rejected the salvation dogma, but embraced the radical notion of egalitarian democracy.

Franklin’s commitment to teach these values was itself something he gained from his Puritan upbringing, with its stress on “inculcating virtue and character in themselves and their communities.” These Puritan values and the desire to pass them on, were one of Franklin’s quintessentially American characteristics, and helped shape the character of the nation. Franklin’s writings on virtue were derided by some European authors, such as Jackob Fugger in his critical work Portrait of American Culture. Max Weber considered Franklin’s ethical writings a culmination of the Protestant ethic, which ethic created the social conditions necessary for the birth of capitalism.

One of Franklin’s notable characteristics was his respect, tolerance and promotion of all churches. Referring to his experience in Philadelphia, he wrote in his autobiography, “new Places of worship were continually wanted, and generally erected by voluntary Contribution, my Mite for such purpose, whatever might be the Sect, was never refused.” “He helped create a new type of nation that would draw strength from its religious pluralism.” The evangelical revivalists who were active mid-century, such as Franklin’s friend and preacher, George Whitefield, were the greatest advocates of religious freedom, “claiming liberty of conscience to be an ‘inalienable right of every rational creature.'” Whitefield’s supporters in Philadelphia, including Franklin, erected “a large, new hall, that … could provide a pulpit to anyone of any belief.” Franklin’s rejection of dogma and doctrine and his stress on the God of ethics and morality and civic virtue made him the “prophet of tolerance.” Franklin composed “A Parable Against Persecution”, an apocryphal 51st chapter of Genesis in which God teaches Abraham the duty of tolerance. While he was living in London in 1774, he was present at the birth of British Unitarianism, attending the inaugural session of the Essex Street Chapel, at which Theophilus Lindsey drew together the first avowedly Unitarian congregation in England; this was somewhat politically risky, and pushed religious tolerance to new boundaries, as a denial of the doctrine of the Trinity was illegal until the 1813 Act.

Although Franklin’s parents had intended for him to have a career in the Church, Franklin as a young man adopted the Enlightenment religious belief in deism, that God’s truths can be found entirely through nature and reason. “I soon became a thorough Deist.” As a young man he rejected Christian dogma in a 1725 pamphlet A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain, which he later saw as an embarrassment, while simultaneously asserting that God is “all wise, all good, all powerful.” He defended his rejection of religious dogma with these words: “I think opinions should be judged by their influences and effects; and if a man holds none that tend to make him less virtuous or more vicious, it may be concluded that he holds none that are dangerous, which I hope is the case with me.” After the disillusioning experience of seeing the decay in his own moral standards, and those of two friends in London whom he had converted to Deism, Franklin turned back to a belief in the importance of organized religion, on the pragmatic grounds that without God and organized churches, man will not be good. Moreover, because of his proposal that prayers be said in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, many have contended that in his later life Franklin became a pious Christian.

Dr Richard Price, the radical minister of Newington Green Unitarian Church, holding a letter from Franklin

According to David Morgan, Franklin was a proponent of religion in general. He prayed to “Powerful Goodness” and referred to God as “the infinite”. John Adams noted that Franklin was a mirror in which people saw their own religion: “The Catholics thought him almost a Catholic. The Church of England claimed him as one of them. The Presbyterians thought him half a Presbyterian, and the Friends believed him a wet Quaker.” Whatever else Franklin was, concludes Morgan, “he was a true champion of generic religion.” In a letter to Richard Price, Franklin stated that he believed that religion should support itself without help from the government, claiming, “When a Religion is good, I conceive that it will support itself; and, when it cannot support itself, and God does not take care to support, so that its Professors are oblig’d to call for the help of the Civil Power, it is a sign, I apprehend, of its being a bad one.”

In 1790, just about a month before he died, Franklin wrote a letter to Ezra Stiles, president of Yale University, who had asked him his views on religion:

As to Jesus of Nazareth, my Opinion of whom you particularly desire, I think the System of Morals and his Religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw or is likely to see; but I apprehend it has received various corrupt changes, and I have, with most of the present Dissenters in England, some Doubts as to his divinity; tho’ it is a question I do not dogmatize upon, having never studied it, and I think it needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an Opportunity of knowing the Truth with less Trouble. I see no harm, however, in its being believed, if that belief has the good consequence, as it probably has, of making his doctrines more respected and better observed; especially as I do not perceive that the Supreme takes it amiss, by distinguishing the unbelievers in his government of the world with any particular marks of his displeasure.

On July 4, 1776, Congress appointed a three-member committee composed of Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams to design the Great Seal of the United States. Franklin’s proposal (which was not adopted) featured the motto: “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God” and a scene from the Book of Exodus, with Moses, the Israelites, the pillar of fire, and George III depicted as pharaoh. The design that was produced was never acted upon by Congress, and the Great Seal’s design was not finalized until a third committee was appointed in 1782.

Thirteen Virtues

Franklin bust in the Archives Department of Columbia University in New York City

Franklin sought to cultivate his character by a plan of 13 virtues, which he developed at age 20 (in 1726) and continued to practice in some form for the rest of his life. His autobiography lists his 13 virtues as:

- “Temperance. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.”

“Silence. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.”

- “Order. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.”

- “Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.”

- “Frugality. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.”

- “Industry. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.”

- “Sincerity. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.”

- “Justice. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.”

- “Moderation. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.”

- “Cleanliness. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, clothes, or habitation.”

- “Tranquility. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.”

- “Chastity. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.”

- “Humility. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.”

Franklin did not try to work on them all at once. Instead, he would work on one and only one each week “leaving all others to their ordinary chance.” While Franklin did not live completely by his virtues, and by his own admission he fell short of them many times, he believed the attempt made him a better man contributing greatly to his success and happiness, which is why in his autobiography, he devoted more pages to this plan than to any other single point; in his autobiography Franklin wrote, “I hope, therefore, that some of my descendants may follow the example and reap the benefit.”

Slavery

When Franklin was young, African slavery was common and virtually unchallenged throughout the British colonies. During his lifetime slaves were numerous in Philadelphia. In 1750, half the persons in Philadelphia who had established probate estates owned slaves. Dock workers in the city consisted of 15% slaves. Franklin owned as many as seven slaves, two males who worked in his household and his shop. Franklin posted paid ads for the sale of slaves and for the capture of runaway slaves and allowed the sale of slaves in his general store. Franklin profited from both the international and domestic slave trade, even criticizing slaves who had run off to join the British Army during the colonial wars of the 1740s and 1750s. Franklin, however, later became a “cautious abolitionist” and became an outspoken critic of landed gentry slavery. In 1758, Franklin advocated the opening of a school for the education of black slaves in Philadelphia. After returning from England in 1762, Franklin became more anti-slavery. By 1770, Franklin had freed his slaves and attacked the system of slavery and the international slave trade. Franklin, however, refused to publicly debate the issue of slavery at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Franklin tended to take both sides of the issue of slavery, never fully divesting himself from the institution.

In his later years, as Congress was forced to deal with the issue of slavery, Franklin wrote several essays that stressed the importance of the abolition of slavery and of the integration of blacks into American society. These writings included:

- An Address to the Public (1789)

- A Plan for Improving the Condition of the Free Blacks (1789)

- Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim on the Slave Trade (1790)

In 1790, Quakers from New York and Pennsylvania presented their petition for abolition to Congress. Their argument against slavery was backed by the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society and its president, Benjamin Franklin.

Death

The grave of Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Franklin suffered from obesity throughout his middle-aged and later years, which resulted in multiple health problems, particularly gout, which worsened as he aged. In poor health during the signing of the US Constitution in 1787, he was rarely seen in public from then until his death.